Originally published on Spoonfed, May 2012.

One of the strangest exhibitions in a while, but still deeply rewarding. Tom Jeffreys reviews Writing Britain at the British Library.

Writing Britain – the British Library’s exploration of the relationship between this country’s literature and its landscape (in the broadest sense of that term) – is possibly the most problematic exhibition I’ve seen in a long time. That’s not to say it’s bad, necessarily; simply that it’s so focused, so specific in its field of view, as to be at first simply disorientating, and by the end bordering on the boring. At many moments in between, however, it really is a joy – and will leave me frenetic with ideas long after most exhibitions have faded from thought.

The problem, and this might sound perverse, is the books. Reading is predominantly a private activity, one best carried out in comfort, so there’s something very strange about being forced to read whilst standing up in a public institution, hunched and peering darkly into glass vitrines. Yes, this is an exhibition in a library, and yes it’s about literature, but it’s so relentlessly text-heavy (texts to describe texts that describe texts) that it becomes exhausting. In addition, the exhibition offers very little in the way of variety – there’s not much going on visually, the audio, video and other gadgetry is fairly half-hearted and the installation (sections separated by large printed banners) feels oddly slapdash.

This near-exclusive focus on books creates two further problems. The first is that it’s largely impossible for more than one person to appreciate any one piece at a time (like reading over someone’s shoulder on the Tube) so it won’t be much fun if it gets busy. It takes me two hours to go round (it could have been much longer) and that’s at the relative calm of the media view.

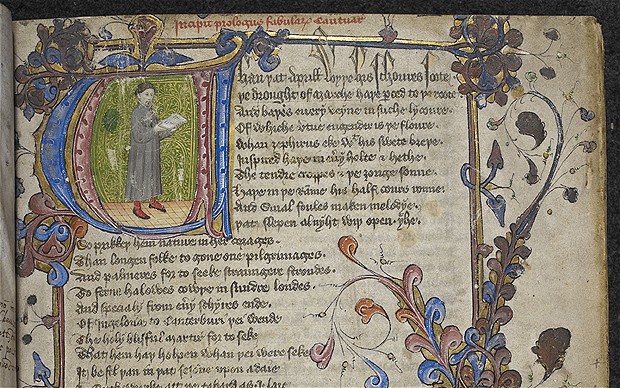

The second is more complicated: an irreconcilable tension between text as signifier and text as object. By placing a book in a museum you foreground its status as object, and whilst there are certainly some impressive inclusions here – from JK Rowling’s manuscript for Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone to handwritten and annotated drafts by Oscar Wilde, John Lennon, John Keats, Emily Bronte and Thomas Hardy – only rarely is this object-status enlarged upon (like the anecdote about James Scott, Charless II’s illegitimate son). The problem for curators more interested in the content of the text (unlike those of, say, Royal Manuscripts) is that the context (books closed to show off their covers or only open on one page) requires the presence of so much secondary summarising text. The result is that, in many cases, the book retains its secrets. But then maybe that’s always the case.

And yet, despite these criticisms, Writing Britain emerges as something surprisingly brilliant. Sensibly split thematically rather than chronologically, the exhibition meanders from myths, legends and the (largely constructed) bucolic idyll via the industrial revolution to man’s relationship with a wild, untameable (equally constructed) nature. There’s also sections on London and suburbia before a subdued but thoughtful finale crystallised in the understated melodrama of Graham Swift’s lovely line: “however much you resist them, the waters will return”.

What such concentrated focus on the book does do is allow for many tiny moments of magic – little flashes that could easily be lost in in a more forthright exhibition. To pick out just a few: Kipling’s delightful description of a cuckoo “singing his broken June tune”; AE Housman’s monumentally dull diary entries of 1981 (simply listing the daily temperature ); GK Chesterton’s marvellously pompous sketches for The Napoleon of Notting Hill; Thomas Gray’s atlas, annotated, hilariously, with a list of “the antiquities of Monmouthshire”; Ted Hughes’ fishing map of the River Taw in Devon; David Mitchell’s wonderfully humble “London is a language. I guess all places are.”; the incomparable brilliance of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Epithalmion, packed with phrases like “branchy bunchy bushybowered wood”; and Ernest Jones’s nineteenth century prison diary drawings and extracts from The Factory Town, with its vividly angry descriptions of “fellow workmen, flesh and iron”.

Throughout, the exhibition explores what curator Jamie Andrews describes as “a feedback loop” between Britain and its writers. The central point – and it’s a good one – is that literature does more than simply describe, it also shapes and creates. This is pinpointed through a number of little intertextual moments – William Wordsworth’s trouble with tourists most obviously, as well as Alan Garner’s co-option of Gronw’s Stone. There’s a particularly lovely moment when the use of the word ‘fleece’ in Ted Hughes’ Wild Rock is suggestively linked to John Dyer’s weird poem about the wool trade, The Fleece. It’s a delightful moment – all the more interesting for its quietness and ambiguity.

Touches like this speak of passionate, extremely knowledgeable, probably quite geeky curators – ones possibly more interested in books than people. Writing Britain is deeply flawed as an exhibition, but somehow it feels the more charming because of it. In the final analysis, this is less a rich visitor experience than a shimmeringly brilliant thesis or series of publications (with an inspirational bibliography). That visitors are asked to work surprisingly hard makes the rewards all the more treasured: if literature is the institution that keeps its secrets, then here is where so many are stowed.

Writing Britain is at the British Library from 11th May to 25th September 2012.