The re-evaluation of an artist’s reputation is always a complex process, and an interesting one. Tate Britain did a good job recently with John Martin, the master of Romantic melodrama, although in truth his bombastic imagery had long been part of the nation’s consciousness. Now it’s the turn of the Royal Academy, who this week open an exhibition in the Sackler Wing devoted to the works of Johan Zoffany. Zoffany (who, incidentally, died when Martin was 21) was, as a favourite of George III, one of the most prominent painters of his age, but since his death his reputation has taken a bit of a hit, with Gainsborough and Reynolds continuing to hold sway as the big names of eighteenth century painting.

According to the Guardian, Tate Britain were due to host a big Zoffany exhibition back in 2010 but then changed their minds, and it’s probably just as well. Zoffany’s biography dovetails nicely with that of the Academy itself, so it makes sense for the revival to begin here. Even though the Sackler Wing is a little pokey – and some sections of this show are particularly cramped – the relationship between Zoffany and the origins of the Academy is intriguing enough for this to be the right place for the show. Apparently he refused to submit to the newly founded Academy’s vetting process, but was instead personally nominated by the king – a sign, admits the exhibition’s curator with refreshing candour, that “the Academy needed Zoffany more than Zoffany needed the Academy”.

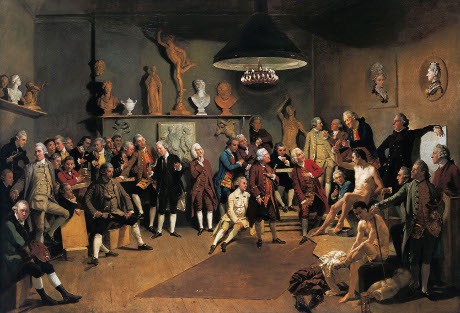

Born near Frankfurt in 1733, Zoffany made his name painting pleasant ‘conversation’ pieces of the great and the good – characterised by a supposedly relaxed atmosphere. Certainly compared to the very formal, official portraits by the likes of Gainsborough, Zoffany’s depictions of the aristocracy take a less adulatory attitude towards rank. As something of an outsider, the curators remind us, Zoffany spots details that others may not, and seems to enjoy showing a more ‘human’ side to George III and Queen Charlotte among others.

Nonetheless, despite the apparent desire for the ‘natural’, many of the paintings here are clunky and rather stiff. In particular: the early religious and mythological paintings including an eroticised David with Goliath’s head; various depictions of the children of the Earl of Bute; and one portrait of and Sir Lawrence Dundas and his grandson, with its weirdly skewed perspective on the right-hand side of the painting.

The problem is that the more supposedly naturalistic the scenes, the more stilted and forced they begin to feel, as the subjects appear like wedding guests posing awkwardly for a photograph, and Zoffany’s attention shifts, despite the curators’ assertions to the contrary, towards the minutiae – the carpets, the gilt frames, the musical instruments that populate his highly detailed depictions of high society. Horace Walpole went so far as to describe one particular painting of George III with his family as “ridiculous” and, as the author of The Castle of Otranto, he can be trusted to know ridiculous when he sees it.

What this means is that Zoffany is actually at his best when the works directly explore their own ridiculousness. And Zoffany is clearly a man with a sense of humour: distinguished art critics ogle the bottom of a sculpted Venus; the East India Company’s John Graham is shown as a fat, lazy layabout; and the artist himself is shown dressing up as a friar for a night of revelling (condoms hanging on the wall behind).

This sense of the ridiculous extends to a broader exploration of theatricality. Among the exhibition’s highlights are his various depictions of David Garrick, particularly a hilarious painting of him as Macbeth, in which the actor’s face is a brilliant parody of creased-brow worry – not dissimilar, now I think about it, to David Cameron when he’s doing his concerned face. Such works remind me of contemporary artist Stuart Pearson Wright, who has also made his name painting actors – like Keira Knightley and Daniel Radcliffe. Whether or not Zoffany shared Pearson Wright’s deliberate desire to draw attention to the process of representation and underline the performativity of identity construction, the effect is still similar. Identity – particularly royal identity – is an endless procession of performance and presentation.

To this end, the exhibition’s most famous work – The Tribuna of the Uffizi – is also its unquestioned high point. Packed with sumptuous detail, its dense composition and vivid colours instantly memorable, it’s a fascinating work for all number of reasons. What really excites me however is the way in which the works of art depicted have as much life as the figures who examine them. Painted characters seem to pop from the walls. In particular, if you look very closely, on the right-hand side just to the left of the Venus, a man’s green sleeve seemingly overlaps the gilt frame that houses him. It’s an incredible moment, possibly a mistake, but one that for me, holds together Zoffany’s entire career: his portraits may be stilted and false, but as art spills over into life, identity is exposed as the performance it is. Art, theatre, society, life – all arise from a series of poses, and none can ever be anything as simple as ‘authentic’. In all forms of representation, parody is always potentially present.

Johan Zoffany RA – Society Observed is at the Royal Academy from 10th March to 10th June 2012.

Image credit: Johan Zoffany, The portraits of the Academicians of the Royal Academy, 1771-2. Oil on canvas, 100.1 x 147.5 cm, The Royal Collection, The Royal Collection Copyright 2011, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II