Originally published on Apollo, 11th February 2014.

‘Discovery,’ we’re told in one of many wall texts dotted about amid the sumptuously carved wooden splendour of Two Temple Place, ‘is seldom a single event.’ It’s one of several illuminating moments in ‘Discoveries: Art, Science and Exploration’, a new exhibition that brings together a diverse array of objects from across the eight museums of Cambridge University and puts them on display in central London.

As co-curator Nicholas Thomas writes in the accompanying catalogue: ‘The exhibition is concerned to enlarge our sense of what discovery was, is, and can be.’ Thomas, the Director of Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, is also the author of a 2003 book about Captain Cook, also entitled Discoveries, so this is clearly a long-running passion.

So does the exhibition succeed in these aims? Up to a point. It’s certainly full of some fascinating objects, many of which are as interesting for their back stories as for their intrinsic properties. A case in point is a tiny Tinamou egg, originally found in Uruguay and then rediscovered by Liz Wetton in 2009. You can only begin to imagine her excitement as she unearthed the little egg, like cracked chocolate, from some dusty cabinet, and first read the handwriting on its delicate shell: no less a name than ‘C. Darwin’. The reason for the crack, we told, is that the great man placed it in too small a box.

This little broken object is something of a high point, and one which I’m not entirely sure the exhibition reaches again. That’s not to say that there aren’t some amazing pieces elsewhere: a beautiful orrery from the 1780s; a huge, 120 million year-old ammonite; a bizarre but rather brilliant piece by contemporary Inuit sculptor Thomas Akilak; and a series of eerily enchanting ‘Muggletonian’ prints from 1846 by Isaac Frost that seek to replace the Earth at the centre of the universe. They’re amazing.

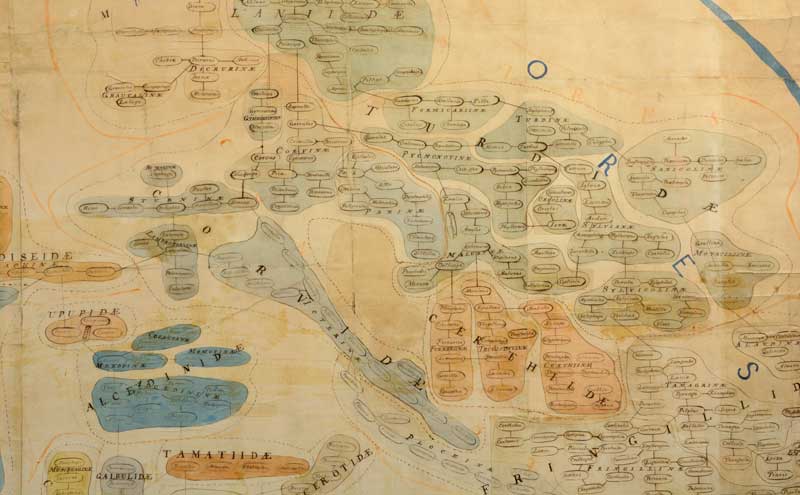

My personal highlight, however, is an apparently artless wall-mounted chart. Produced by Hugh Strickland in 1843, it attempts to provide an overview of the ‘Natural affinities of Birds’. A patchwork of paper with brown ink notations, layered over in certain sections with washes of watercolour, it forms a kind of map – one that represents the natural world named, grouped, linked, and neatly colour-coded. We have Falconidae and Vulturidae at the top; Pelecanidae at the bottom. Despite possibly being on public display for the very first time, we’re told that this chart contributed to the stabilisation of natural history terminology.

And once terminology is stabilised, new knowledge emerges. Strickland’s aim, we’re told, was not to demonstrate actual relationships in nature, but to provide ‘a guide to the arrangement of specimens in a museum display’. And yet, it’s fascinating to think that, through Darwin just a few years later, the latter was retroactively imposed upon (and/or found within) the former. Nature was found neatly to conform to the pre-existing systems for its display. The museum stood as both protector and originator of knowledge.

The trouble with ‘Discoveries’ is that it is never quite able to function in the same way. It contains several lovely moments, but never really comes together to contribute any more than the sum of its parts. Instead, it begins to feel like an extended marketing exercise for the eight Cambridge museums involved. It is perhaps no coincidence that the exhibition has received funding from both Arts Council England (currently under investigation by the Culture, Media and Sport Commons Select Committee for ‘geographical distribution of funding’) and the Bulldog Trust, who own Two Temple Place, and whose exhibitions aim to ‘enable institutions around the UK to showcase what makes them special’.

More focus on the first word of the exhibition’s subtitle may have helped. There’s precious little art here, barring a few minor modernist works, a tiny Henry Moore, and two divine photograms by Sophy Rickett, looking exquisite against wood panelling and an old brass telescope. That lovely moment aside, art is presented largely within the defining framework of scientific knowledge – either as effective communicator, if ‘correct’, or quaint example of historical ignorance, if not. On the landing, some very bland portraits of various museum founders contribute little.

Without the self-questioning that art (amongst other strategies) could have provided, what we’re left with is a disparate assembly of objects of varying degrees of interest. This may be an exhibition full of discoveries, but they have all already been made.

‘Discoveries: Art, Science and Exploration from the University of Cambridge Museums’ is at Two Temple Place, London, from 31 January–27 April 2014.