Originally published on Spoonfed.co.uk, April 2008

Somebody once told me that the only difference between comedy and tragedy is where you choose to end the story. In ‘Life Before Death’ at the Wellcome Collection, every story ends with death.

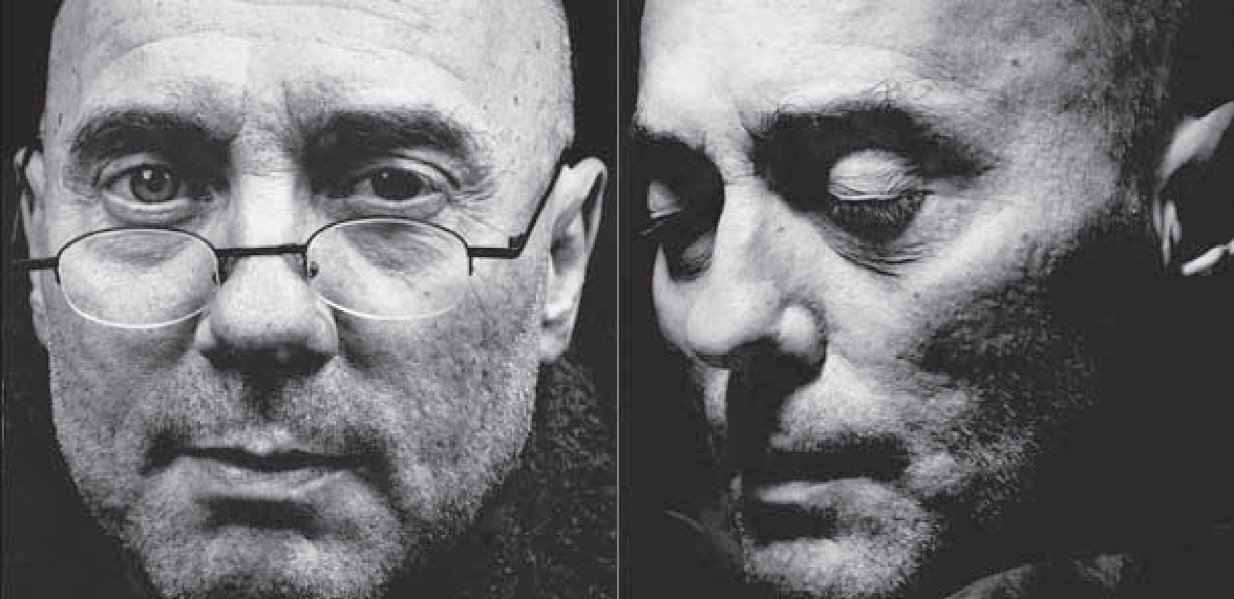

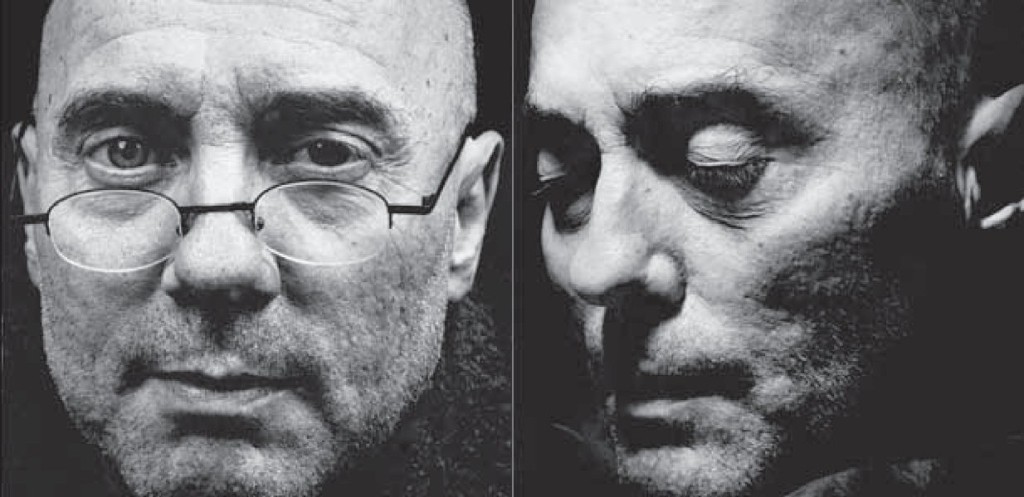

Photographer Walter Schels and journalist Beate Lakotta have spent a year interviewing 24 terminally ill people in the days and weeks before their death. Each person is represented in the exhibition by two photographs – one taken shortly before their death, the other shortly after – and about 150-200 words of text outlining their story. That is all. In some ways this is a stark and clinical exhibition – every photograph is black and white, the same size, framed in the same way – not dissimilar to the institutional context in which these people spent their last days and weeks.

But, by nature, this is also an intensely personal project not only (obviously) for the dying and their families but also for the artists themselves. Schels and Lakotta are a couple whose relationship has always been marked by the spectre of death. Schnels is significantly older than Lakotta and the pair have long been conscious of what might happen were one of them to die. Conceived in part as a way to address the ever-presence of death, ‘Life Before Death’ is in some ways as much about the artists as it is about death, or indeed, life.

It is this dichotomy between the personal and the public that lies at the heart of ‘Life Before Death’. Death is a uniquely private moment that happens just to the individual, but it takes place largely within the confines of a public institution. In the same way, the project is housed in a publicly accessible exhibition space, but the experience of viewing the work on show is intensely personal, silent and internal.

The relationship between the personal and the universal is something we see each of the subjects grappling with in their own very different ways. At times of crisis, people resort to repetition as a potential path to something larger and more meaningful. Some resort to religion, some to poetry, others to cliché. Wolf-Bernd Januszewski’s wife Ingrid appeals to a familiar uncertainty – ‘one of these days we’ll be happy together again, for ever and ever’ – whilst Irmgard Schmidt quotes Goethe. For some, like Ingrid, this provides comfort. For others, like Gerda Strech, the search for significance only leads to pain. ‘Oh, don’t talk to me about souls’, she says. ‘Where is God now?’

The stories on show are amazing in terms of their diversity. There is panic, hope, unbearable sadness, needle-prick humour: Klara Behrens has only days to live but her overriding thought is that she’s only just bought a new fridge-freezer. ‘If only I’d known…’ she says.

There is no unifying thread. There is no overarching narrative that can explain death to us. Religion has tried to provide one, and failed. So too has science. So too art. The artists deserve credit for not trying to impose any of these things, not even the value of their own project. This strategy suggests that – despite all the hospitals and the churches, the laboratories and the cemeteries, the poems and the prayers – death is simply something humanity cannot cope with in a single coherent fashion.

One story struck me in particular, that of ad-man Heiner Schmidtz. When his colleagues come to visit him they act as if everything is normal: they drink, smoke, have a bit of a party. ‘No one asks me how I feel’, says Schmitz. ‘Because they’re all shit scared. I find it really upsetting the way they desperately avoid the subject, talking about all sorts of other things. Don’t they get it? I’m going to die! That’s all I think about, every second when I’m on my own.’

As fascinating as the stories are, it is the photography that makes them real, by giving the viewer a face to latch on to. Again the emotional variety is amazing: there’s the button-bright sadness in the eyes of 82 year old Irmgard Schmidt for example, or the eerie spiritual calm of Maria Hai-Anh Tuyet Cao. That every work is in black and white automatically evokes the past, something or someone that is no more. And the use of super high-detail close-up is both revealing and futile: as if through extreme proximity one might be able to see past the flesh to some kind of truth within or beyond.

This is, I think, one of the most powerful exhibitions I have ever been to. And with its careful balance between the arts and the sciences, with its ambition but lack of bombast, the Wellcome Collection is the perfect place to host it. If I were a didactic sort, I’d say that it’s something that everyone ought to go to. Because, somehow, this is more than just some photographs and some short stories. Reading them back now on my computer, the power is sort of there, but there’s a loss of dignity somehow. It is as if, even for this most private of projects, the proper place is indeed a public one.

The actual act of viewing the before/after format of the photographs is fascinating: both life and its absence are captured by the camera’s eagle eye. But where is death? The actual moment of death is still absent, slipping in the vacant white wall-space between each image. Despite the intense close-up focus on death, the attempt to locate it, measure it, understand it, it has still, somehow, escaped. Death is never quite there; it is always there.